Automobile Visionary Preston Tucker’s Downriver Roots

Automobile Visionary Preston Tucker’s Downriver Roots

By Karin Risko

Preston Tucker, who aspired to build a revolutionary “car of tomorrow,” was one of the last automotive visionaries to attempt to break into the competitive, exclusionary and often ruthless world of automobile manufacturing. His quest gained him worldwide notoriety and, allegedly, the wrath of the Big Three.

Even today, nearly 65 years later, Tucker’s legacy is shrouded in controversy and conspiracy theories. The “Tucker myth” skyrocketed further when his story went Hollywood in 1988 with the release of the Francis Ford Coppola movie Tucker: The Man and his Dream featuring actor Jeff Bridges as Preston Tucker.

While Tucker may be somewhat of a legend, many people don’t realize he has roots Downriver. Even the movie about his life skipped his Lincoln Park years.

Downriver Years

Born in Capac, Michigan in 1903, Preston, his mother, Lucille, and brother, William, moved to the Detroit area when he was a young boy following the tragic death of his father in a railroad accident.

Old Mellus Newspaper articles indicate Tucker was 13 years old when he began his first job as an office boy for D. McCall White, vice president of engineering for Cadillac Motor Car Company. Working for White, Tucker learned engine and chassis design while attending Cass Technical High School where he studied engineering, commercial law and business management in college extension courses.

Although Tucker’s mother taught school in Lincoln Park (believe it was considered Ecorse Township Schools then), it’s not clear when the family first moved here. Records show Tucker joined the Lincoln Park police force in 1923, at age 17, much to his mother’s chagrin. Eleven months later, he had to quit after his mom informed the police chief that Tucker falsified his papers and was underage.

He rejoined the force in 1925, along with his buddy, Floyd Crichton, who later became Lincoln Park police chief and a trusted advisor in the Tucker Corporation.

A motorcycle patrolman, Tucker was known for his mischievous antics and mechanical aptitude. He was always tinkering with his vehicles to make them run faster and took great pride in catching motorists who tried to outrun him. According to local lore, irate residents frequently complained to village officials (Lincoln Park was still a village) about his speeding down Fort Street and performing daredevil stunts.

One cold winter night, Tucker’s need for heat in a new heater-less police touring car – and his ingenious quick fix – raised the ire of village officials. Intent on capturing engine heat to stay warm, Tucker used a blowtorch to cut a hole in the car’s firewall. The village president called his inventive solution “damage” and temporarily suspended him.

Trouble didn’t always trail the handsome and exuberant cop. Tucker received accolades for his police performance too. One local newspaper reported that Tucker “single-handedly captured two gunmen in an automobile chase and battle that extended from Lincoln Park to Wyandotte.” Using one hand to steer and the other to return fire, he doggedly pursued and apprehended the fleeing criminals. Just like in the movies, eh?After three years, Tucker left the police department and began to hone his skills in the automotive industry. In 1935, he made an unsuccessful bid for mayor of Lincoln Park. During the campaign, he penned a passionate letter to his “friends and fellow citizens of Lincoln Park” stating: “The boost in dollar wages and the cut in human was a BLINDFOLD march to the depression in which we are mired today.”

He further implored citizens to “Finally, let’s all together save our homes, protect our laborer and farmer; save our business; our machinery and factories, upon all of which we ultimately depend.”

Although Tucker’s quest to build an automobile company took him away from Lincoln Park, he still returned to the city on numerous occasions.

One such special visit occurred in 1948. After his son Preston Junior’s wedding reception at the Dearborn Inn, Tucker headed to Lincoln Park City Hall where he planned to show off the new Tucker ’48 to hometown folks. Accompanying him in his prized vehicle was Vera, his wife, and long-time friend William S. Mellus, publisher of The Mellus, a once popular Downriver newspaper headquartered in Lincoln Park.

The car broke down on Southfield Road. Not to be stymied by mechanical problems, Tucker, still dressed in his formal attire, got out of the car and tinkered with the engine until it started running again. Tucker proudly drove on to city hall where “the waiting throng” received him and his car “with cheers.”

Tucker Legacy

Dubbed a charismatic visionary by supporters and a con artist by detractors, this controversial and outspoken figure appeared to be on the brink of building an exciting and innovative automobile company when he founded the Tucker Corporation in 1946.

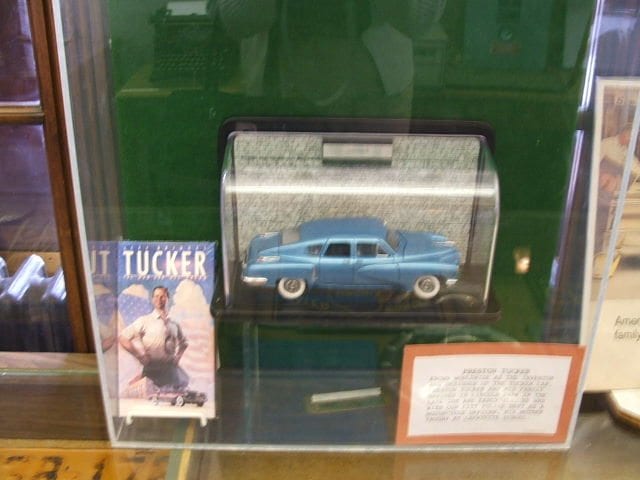

“Ten years ahead of the future” is how author Charles T. Pearson described the futuristic looking Tucker ‘48 in his book The Indomitable Tin Goose.

Not only was the car attractive and economical, it possessed features not found on cars of this era such as an air-cooled rear engine, disc brakes, and an independent four-wheel suspension. These once innovative features have become standard equipment in later model cars.

A trailblazer in automotive safety, Tucker was critical of other automobile manufacturers whom he believed neglected safety in favor of visual appeal. The Cyclops Eye, the trademark Tucker center headlight, was designed to provide drivers with better visibility when turning. Other safety features included a padded dashboard, seatbelts, and a pop-out safety windshield.

While Tucker’s ideas appeared ingenious on paper, execution proved to be difficult and costly. Plagued with production problems, financial woes, employee dissention and the onslaught of federal fraud indictments by the Securities and Exchange Commission, the fledgling Tucker Corporation closed its doors. Tucker’s dream ended with the production of only 51 cars.

Tucker, who died in 1956 of lung cancer, often used the phrase “a hair away” to describe how close he had come to realizing his vision.

Did Tucker simply underestimate the cost of launching an automobile company? Did he squander and mismanage investors’ money? Were the series of fraud charges initiated by the Securities and Exchange Commission legitimate or part of a cleverly concealed anti-Tucker smear campaign instigated by the Big Three automotive manufacturers to drive him out of the industry?

Was he a genius thwarted by conspiracy or a masterful promoter out to swindle people? I don’t care to speculate. I do know, however, that it’s exciting and a source of local pride to know this colorful and influential innovator was part of our community.

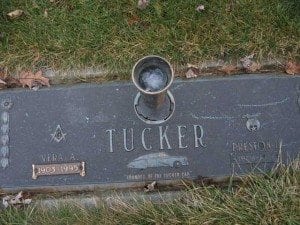

We can also pay homage to this fascinating figure at his final resting spot in Flat Rock where a simple rectangular plaque in the Masonic Gardens section of Michigan Memorial Park marks Preston Tucker’s grave. A relief image of the famed Tucker ’48 along with the inscription “Founder of the Tucker Car” is etched into the marker immortalizing the “kid cop” from Lincoln Park and his dream forever.

What if the “kid cop” from Lincoln Park had actually succeeded in his quest to build a new type of car? How different would the auto industry and our world be today?

Karin Risko is the founder of Hometown History Tours. A major proponent of amping up heritage tourism within our region, Karin tells the vibrant story of southeast Michigan through a variety of tour offerings. Her newest tour offering Southeast Michigan Sightseeing Tour brings the magic of “Pure Michigan” to our region.